Websites Are Like Video Games

No slides found on page

THIS IS UNPUBLISHED - Please don’t share any links to this yourself, as the content is likely to change

Websites Are like Video Games

It’s all about the frame times!

Freyja Domville (she/they)

Bluesky: @freyjadomville.co.uk

Blog: https://freyjadomville.co.uk

Hi, I’m Freyja, these are the places you can reach me at to see what I’m up to or how I’m doing. My pronouns are she/they

This is a diatribe

Personal opinions/thought processes lie herein

As is customary with my talks, this is one part metaphor and one part “Freyja thought of an analogy”. This might feel like a talk without much of a filter, but I hope to talk about some cool things.

Why is this diatribe worth listening to?

- I have a decade in software development, in teams both large and small 🔟

- My specialisms are in accessibility, UX and performance engineering ⏩♿

Today, we’re going to be leaning on my decade of experience in good UX here, though some of you were here last time, so hopefully that’s in your head from previously

Let’s drink from the UX and performance firehose! 🚒

Contrary to last time, however, we’re gonna be doing a bit of a focus, specifically on what performance means in terms of a good user experience

This is a Steam Deck…

This is my Steam Deck. And what I want to talk about today is related to a perspective change I’ve had over the last two years playing around with it.

Opening my eyes: Mangohud

One thing in particular stuck out to me was the accessibility of performance tools, and the amount of information available to the user. Lots of settings to tweak, lots of configuration to draw from, a tinkerer’s paradise…

What I had before: high-refresh rate gaming

And coming from my own prior experiences, gaming at 60FPS minimum on a 4K display, where the latency was smooth, responsive, with Adaptive Sync, and a good experience.

But with the Steam Deck I was happy with just 40FPS

Celeste was an exception.

Overall, however, I have still had a good experience with the Deck, even when limiting to 40FPS, and found myself gaming more portably away from my desk for long periods of time. Sofas, trains, my bed in the mornings, and I often go long stretches of playing a game with the Steam Deck instead of my main PC, especially after work.

The key is consistency

The two main things that detracted from experience were:

- Screen tearing

- Stuttering

And oddly enough it was consistency that ended up being the thing that helped most with what makes a good experience. Whenever a game stutters, I see that more than I see slow frame rates. Whenever I see tearing/artifacting, the less immersive a game is.

In other words: Not like this!

The reason I often had a better experiences was because I wasn’t trying to run up against limitations of the hardware/software, and the render targets it had.

Browser engines just paint stuff to the screen

- They do so as efficiently as they can, but it’s the same principle.

- They can animate smoothly

- And they’re good at doing it (if developers are mindful)

The more I thought on this, the more I’ve come to the conclusion that websites, or at least a good experience for the, user, is more about consistency rather than going mega fast.

Takeaway: Don’t hog the event loop

- This includes long Promise chains!

- To understand why, see Lydia Hallie’s video on the event loop

In other words, your JavaScript needs to not run for too long, so new updates/ticks can proceed from there

In practice: 40fps is still 25ms

- 60 is 16.66ms

- and 30 is 33.33ms

- so 40 is a good middle-ground between the two

So, what does 40fps mean, in practice? well, it means that every frame you have 25 milliseconds. The frame time is the inverse of the frame rate, so 1/40 is 0.025s, or 25 milliseconds. It makes for a good middle ground to aim for as a minimum level of consistency on your sites that’ll be tolerable.

Low hanging fruit: Slow events

- Look for any events/interactive behaviours that run for more than 25ms

- The thing that slows your frame rate is long running events.

This ultimately means that a common sign of slow performance for a site is that an update/event is doing too much at once and should be broken into smaller pieces.

React: Update your versions

- Concurrent rendering in React 18 is important

- v18 and up also use

scheduler.yield()to co-operate with the browser - Consider moving to React Compiler in v19 (automatic memoisation)

As an aside for React developers who are curious, make sure you’ve updated your versions and you’ve memoised appropriately. That’s all I’m gonna touch on here, but it’ll do a bunch of things for you. React 19 is especially interesting because it’ll automatically memoise state and reduce the amount of activity. Ever wonder why Bluesky’s so fast for a React app?

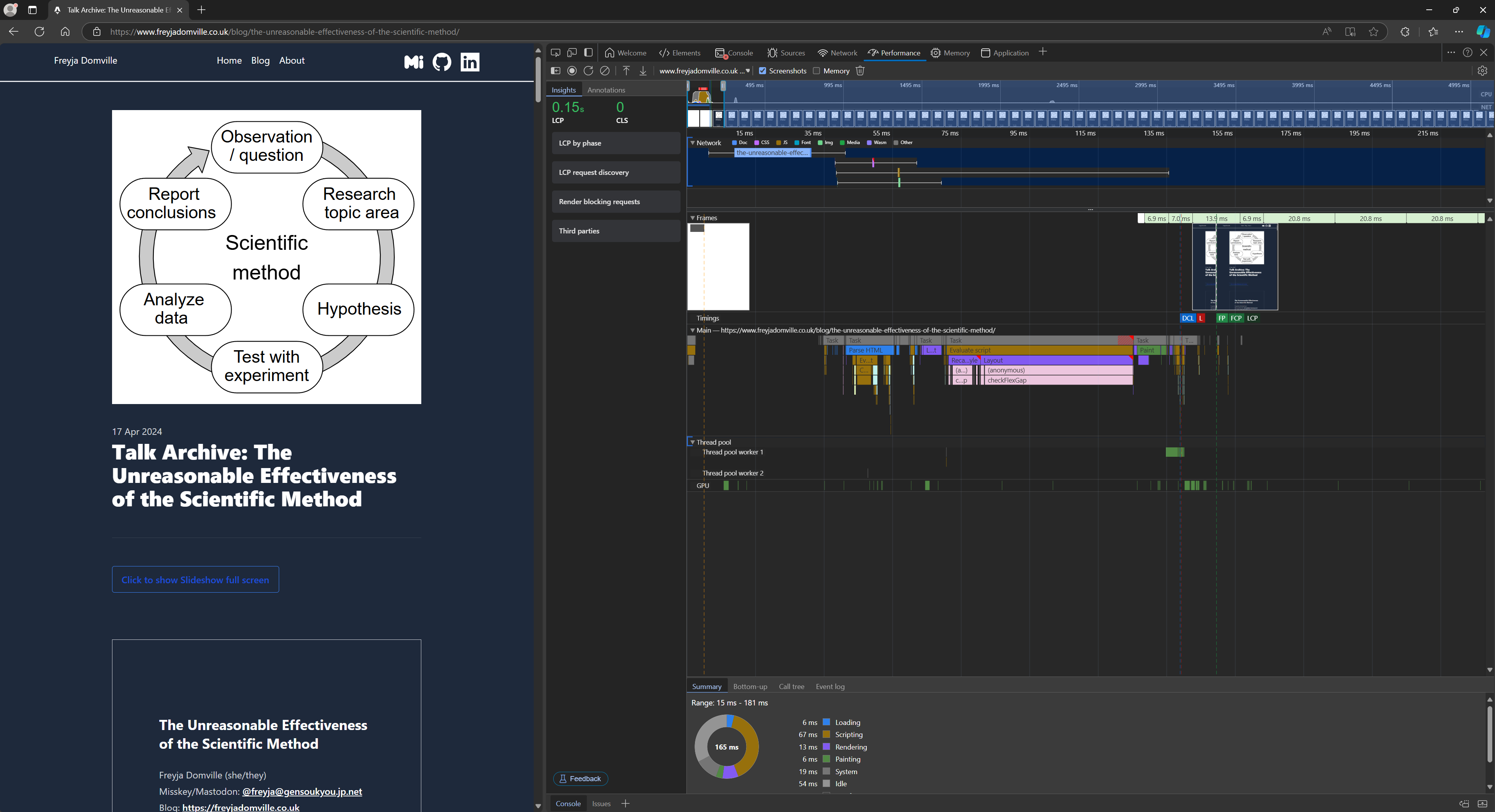

Tip: How to use the Performance tab and flame-graphs

The best way to check all of this is to use a flame graph. It’s essentially a timeline of how your code is behaving and what is taking up the most time. All modern browsers have them built in, and they can highlight the overall performance profile of your application. There are also off-CPU representations (like network I/O in Browsers, but also disk I/O in servers) that can be used to inspect things on the server-side.

The basic premise is this: Are the blocks you’ve got narrow and taking a small amount of time? No? Then you’ve got a potential place to improve your code.

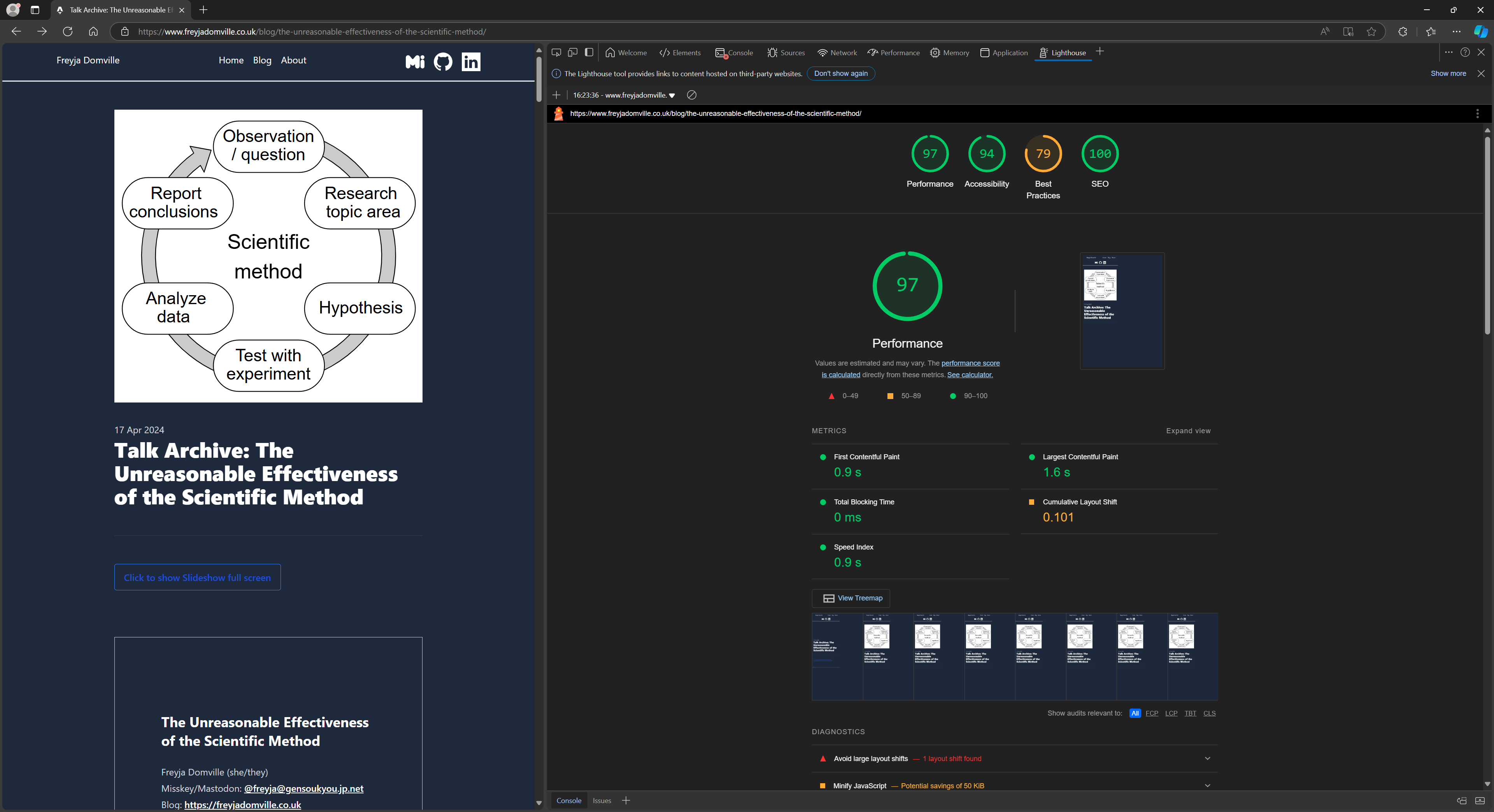

Tip: Use Lighthouse to summarise the data available

Another useful tool to summarise and prioritise things is Lighthouse, available in the Blink browsers, (Chrome and Edge). Also some cool accessibility things, which I’m going to be blogging about separately in the new year.

Perf Test in production!

- Get source maps working well for stack traces if you have to first.

- Testing locally might fall foul of dev mode issues (e.g. StrictMode in React, unminified code)

And finally, the ever present reminder when testing this sort of thing, test in production, otherwise you’re not getting representative data, as servers may not be loaded properly, APIs may no tbe configured correctly, and so forth. additionally, you’re likely running a completely different build, so even local data may not be representative, thanks to different network effects and unminified JavaScript.

As with all good dev practice, this is iterative.

- Getting an overview of how something works is important.

- You’re probably optimising in the wrong place.

- This is how I measure (even on servers where possible)

To start to sum up, this is basically how I think about websites now. It’s an iterative process to get things where they need to be, and using tools like this, and framing your symptoms with an angle of “is this good enough” helps with priority.

Always measure, and always test with representative devices.

- More info in the slides of my previous talk.

- This is ever changing, and getting to continuously test this is important.

This is part of why I have the ideas I do in my previous talk, about “The Scientific Method”. User Experience is an ongoing thing, not just something that’s one and done, as user needs will change, and devices and infrastructure will need to adapt to the load.

I’m looking forward to seeing your thoughts on this - keep me posted of your progress

Freyja Domville (she/they)

Bluesky: @freyjadomville.co.uk

Blog: https://freyjadomville.co.uk\

Thanks for listening! I will not be taking questions. 👋🏼

- Look at the blog post or subscribe to my Bluesky for slide copies and speaker notes